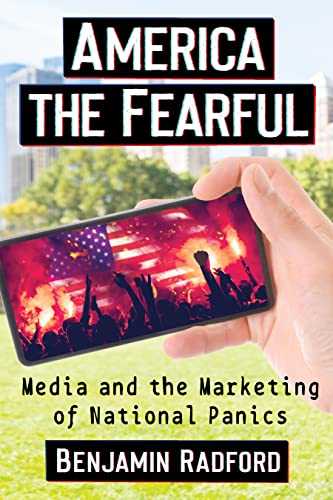

America the Fearful

America the Fearful: Media and the Marketing of National Panics

Author: Benjamin Radford

National panics about crime, immigrants, police, and societal degradation have been pervasive in the United States for most of the twenty-first century. Many of these fears begin as mere phantom fears, but are systematically amplified by social media, news media, bad actors, and even well-intentioned activists. There are numerous challenges facing the U.S., but Americans must sort through which fears are legitimate threats and which are amplified exaggerations.

America the Fearful examines the role of fear in national panics and addresses why many Americans believe the country is in horrible shape and will continue to deteriorate (despite contradictory evidence). Political polarization, racism, sexism, economic inequality, and other social issues are examined. Combining media literacy, folklore, investigative journalism, psychology, neuroscience, and critical thinking approaches, this book reveals the powerful role that fear plays in clouding perceptions about the United States. It not only records the repercussions of this toxic phenomenon, but also offers evidence-based solutions.

Praise for America the Fearful

Chapters

Chapter 1: News Versus Noise

Chapter 2: Half-Empty: American Moral Masochism

Chapter 3: How Media Mangle, Mislead, and Magnify

Chapter 4: Phantom Activism and Social Sabotage: Why Things Don’t Seem to Improve

Chapter 5: Them and Us, Straw Men and Boogeymen

Chapter 6: Science-Based Solutions

Sneak Peek

Introduction

Thing are looking up, both in America and around the world. We are making progress.

Now that I’ve lost all credibility with most socially aware readers, allow me to explain why— and why you probably think I’m wrong.

By most measures the world is improving, from literacy to health, lifespan to gender equality. The idea that the world—including and especially America—is getting progressively better over time has been discussed (and conclusively demonstrated) by eminent writers including Steven Pinker, Michael Shermer, and Hans Rosling. The overall trend is clear and compelling. Martin Luther King Jr. knew this when he wrote, “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

Yet despite years of scholarship presented in specialized reports as well as bestselling books, much of the general public has seemingly refused to accept or internalize this progress, instead plodding along ever-more morosely as each fresh crisis and outrage seems to confirm their assumptions.

There are still calamities, of course; 2020 saw the rise of a global pandemic that killed millions—but also the rapid development of vaccines to end it. The Trump presidency—no friend to either science or compromise—also met its demise as 2020 closed (albeit not without a fitful dying gasp when Trump supporters sieged the Capitol early in 2021). Just as weather is not climate, these setbacks are not emblematic of the course of human history. On an academic level, the evidence seems pretty clear. On a personal level, however, it’s a very different story. Yes, the world has problems. But overall things are good, and getting better. So why do people find it so hard to believe, and reject that message as somehow an impediment to further progress?

This book is an attempt to help answer that question. Pinker and others have provided partial answers, ranging from media manipulation to psychological biases. But the intractability of progressophobia, as Pinker has termed it, merits a closer look.

Beyond Politics

We can begin by looking at the world from a different perspective. Many topics in this book have traditionally been viewed through a political lens. This approach is so common it could be considered the default view, as in the oft-heard phrase “everything is political.” Stanley Fish, dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences at the University of Illinois at Chicago, noted in The Chronicle of Higher Education that “Everything is political in the sense that any action we take or decision we make or conclusion we reach rests on assumptions, norms, and values not everyone would affirm. That is, everything we do is rooted in a contestable point of origin; and since the realm of the contestable is the realm of politics, everything is political. But this sense in which everything is political is so general (no action escapes it) that there isn’t very much that can be done with it.”

So, politics is certainly one way to view the world, but it is hardly the only way—and certainly not the most fruitful way, in part because it often encourages tribalism. Though the Trump administration seemed to usher in a stunning new era of divisive, tribalist thought that damaged America’s ability to work together, our 45th president was not the inventor of this mindset—he simply rode it as long as he could, the way a surfer glides on a wave. If we are to calm the waters in a more lasting way, we must work on a more foundational understanding of what got us, collectively, into the mindset to begin with: the forces at work churning the waves deep below the surface. The approach in this book is multidisciplinary, drawing from seemingly disparate areas including folklore, psychology, sociology, critical thinking, media literacy, and evidence- based research. Like Douglas Hofstadter’s book Godel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid—though I draw no parallels to that book’s importance or insight—my approach relies on the fact that common themes can be revealed by looking in different areas. A confluence of approaches can be—and must be—brought to bear in order to fully apprehend the fear and malaise that plagues America.

American Identity

In some ways the so-called “national conversation” is a (typically circular and fruitless) debate about the nature of America. Each news story, bad or good—though mostly bad, as the news by definition is wont to be—is filtered through increasingly partisan lenses and framed as a talking point for a political agenda. A growing number of independents are rejecting this model, however.

This has been going on for some time but came into sharper focus during the past few politically charged years. When then-candidate Donald Trump’s infamous comments about sexually grabbing women were heard in the Access Hollywood recordings, many cultural critics saw the incident as a clear, indisputable, and high-profile vindication of what they’d been saying for years: misogyny and sexism are deeply entrenched in America. Despite weak protestations by Trump and his surrogates that he didn’t really mean such “locker room talk” (and his later absurd conspiracy theory questioning whether that was really his voice), many viewed it as both sincere and representative of a much broader social problem.

Others, however, including Michelle Obama, steadfastly refused to accept that interpretation. Referencing Trump’s comments in an impassioned speech at an October 13, 2016, Clinton campaign rally in Manchester, New Hampshire, she stated that “This is not normal. This is not politics as usual. This is disgraceful. This is intolerable.” Trump’s lewd comments, Obama averred, were an aberration and did not in fact reflect how most Americans (male or female) talked or thought about women.

Following the mass shooting at a Pittsburgh synagogue in October 2018, Pennsylvania governor Tom Wolf addressed the media and stated that “These senseless acts of violence are not who we are as Pennsylvanians, they’re not who we are as Americans.” Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney tweeted on October 27 that “This is not normal. This is not who we are as a nation.” New Jersey senator Cory Booker, at an October 28 speech at the University of New Hampshire, referenced the synagogue attack and emphasized that “This is not normal. This is not who we are…. Since 9/11 the majority of our terrorist attacks have been rightwing groups and the majority of those have been white supremacist groups, people that are peddling hate against blacks or Jews or other minorities. It’s so antithetical to who we are.” Hillary Clinton echoed the point during an appearance on the Steve Harvey Morning Show in September 2016, discussing systemic racism: “This horrible shooting again? How many times do we have to see this in our country? In Tulsa? An unarmed man, with his hands in the air, this is unbearable and needs to be intolerable. And maybe I can, by speaking directly to white people, say ‘Look this is not who we are.’”

At the same time, however, many people on social media—Democrats and liberals in particular—spread exactly the opposite message with memes about how in America (and especially under the Trump administration), such horrors are inherent in the national character. This is normal, they assert: such violence, sexism, and hatred, sadly, is entirely representative of America. In the wake of the 2021 assault by Trump supporters on the Capitol building, many politicians decried the violence saying that “it’s not who we are” while opinion writers for Politico, The New York Times, and other outlets took the opposite view, insisting that the events precisely describe “who we are” as a country.

Often these are not even differences of opinion based on political ideology (the stereotypical Red versus Blue divide) but are expressed by people within the party. Who’s right? Are mass shootings and violence an inherent and inevitable part of America that represents the true nature of the country and its citizens, or are they aberrations? And, more broadly, is American culture inherently racist and misogynistic, as is often claimed, or is it true that, as Michelle Obama stated, “This is not normal” for our country but instead “disgraceful” and “intolerable”? Did Trump’s mob represent Americans as a whole, or a fringe group? They can’t both be right.

Why are so many people interpreting the world in its polar opposite, embracing a moral masochism that inflates the very worst aspects of humanity? And how did doing so become a virtue? Can democracy thrive—or even survive—in such a world? An informed citizenry is essential to a functioning democracy, and citizens must be able to distinguish truth from fiction in order to make evidence-based decisions about public policy.

The answer lies in the complex interaction of media, psychology, and sociology. In a way, there is nothing new in this book. All the facts and assertions you read here can be—and should be— checked; most are easily available in other books, journal articles, news stories, and other sources referenced. An idea, as Robert Frost observed, is a feat of association. That is, the parts are already there, it’s merely in how you arrange or understand those elements in relation to one another that insight emerges. And new insight can bring hope to many weary Americans who have found themselves drowning in this often-paralyzing, fear-based worldview.

Once we challenge these assumptions we can open our eyes to new ways of thinking and behaving. As Marcel Proust observed in Remembrance of Things Past (1923), “The only true voyage of discovery, the only fountain of Eternal Youth, would be not to visit strange lands but to possess other eyes, to behold the universe through the eyes of another…” With this book I hope to provide other eyes, or at least lenses that can help correct the myopic malaise that has lately so thoroughly saturated our collective American psyche. Those of you who hesitate to accept such a claim, who have a deep pang in your conscience that tells you such optimism is somehow wrong—it denies or minimizes the suffering of victims, the plight of the underserved and oppressed—can perhaps take comfort in the fact that you will learn how and why you have those feelings, that they are a natural product of the current social and media environment, and your own psychological processes. These feelings often stand in the way of making actual positive change in the world, and so examining them is a collective path toward more progress.

Assuming that what people believe matters—since of course it affects how they act and vote if nothing else—it’s important to understand the actual, true nature of the world by going beyond mere opinion and popular misconceptions with recourse to science and statistics. These dueling worldviews can be, and must be, reconciled with the facts. The issue is rarely one of malice; instead it’s people with good intentions who are simply misled—by news and social media; by our increasingly insular circles of friends; and most fundamentally by our brains.

The good news is that in most cases the truth can be discerned with less superficial examination, and we can cut through misinformation to move forward with a clearer, more united purpose. Like critical thinking in general, this process is not some inborn type of intelligence; it is a skill that can be learned and sharpened. Americans face enough real enemies and enough real problems without wasting our time, resources, and mental energy fighting over false or exaggerated claims and (what are often) minor differences of opinion that serve to divide instead of unite. Yet we seem unable to stop doing so.