I recently came across a blog by a fellow cryptozoology writer, Nick Redfern, which began with a well-deserved rant about armchair debunkers. The shabby state of research into Fortean topics is widely acknowledged by skeptics—and some “believers” (for lack of a better word).

In this particular case it was unnamed “debunkers” that he vented some spleen towards: “If there’s one thing, more than any other, that annoys me in the field of paranormal research, it’s an armchair researcher of the debunking kind. Time and time again I have heard the debunkers loudly assert (often in high-pitched, whiny voices, and with their arms firmly folded) that the chupacabra simply cannot, and does not, exist.”

I should note at this point that I may be one of the “debunkers” he’s referring to, as I spent five years investigating the chupacabra; the result was my 2011 book Tracking the Chupacabra: The Vampire Beast in Fact, Fiction, and Folklore, published by the University of New Mexico Press. (For the record, I have never claimed that the chupacabra cannot exist, merely that overwhelming evidence suggests it does not.)

As to these armchair debunkers, he asks: “How do they know? Well, actually, they don’t know. Have they personally visited Puerto Rico? For the most part, no, they have not. Have they sat down opposite a witness and actually spoken to them? Nope: Hardly more than the barest occasion. What they have done is to secure their data from that bastion of truth and reliability known as the Internet…. As to why the debunkers piss me off so much, it’s not just as a result of their lazy approach and attitude. It’s because by not actually visiting the places in question, and speaking with the people on the ground, they are missing out on a wealth of untapped data that simply cannot be found by just opening Google and typing in the words ‘Puerto Rico + chupacabra.’”

I, too, share his annoyance with armchair researchers (of all stripes, especially those who monger mysteries and can’t be bothered to check facts and do more than a superficial analysis). Field investigation is indeed important, and has helped me solve countless mysteries that I would not have been able to do via laptop or from the comfort of my armchair. That’s one reason why I traveled extensively for my chupacabra research, not only in New Mexico and Texas, but also as far as the jungles of Nicaragua. I also made multiple trips to Puerto Rico, interviewing dozens of first-hand eyewitnesses and experts, doing archival research, and so on.

He uses the following example: “A perfect case in point: if the chupacabra is a real creature, ask the naysayers, then why did it suddenly surface out of nowhere in 1995? Well, actually, it didn’t. Yes, it did, they reply; the Internet says so. Well, yes, the Internet does say that. But try speaking to the locals [who admit] that, yes, those emotive words—chupacabra and goat-sucker—were relatively new. No one disputed that. They added, however, that blood-sucking monstrosities of vampire-like proportions had been reported across the island not just for years but for decades; at least since the 1970s.”

I’m not a fan of believing whatever “the internet” says, but in this case it’s not me believing the internet so much as the internet believing me. Tracking the Chupacabra was the first book to establish that the beast first appeared in 1995 (and why). I’m sure there are some whiny-voiced, arm-crossed pouty armchair debunkers who couldn’t find Puerto Rico on a map insisting that the chupacabra suddenly surfaced in 1995, but they’re referencing my work and conclusions, and I stand by them. There seems to be not a single printed reference to a vampiric “chupacabra” in Puerto Rico or anywhere else before 1995; the word was coined soon after the first sighting in August 1995. No one suggests that the chupacabra “surfaced out of nowhere,” as I make very clear in my research; it surfaced in that year due to several factors, most prominent among them the release of the sci-fi film Species; see chapter 7 in my book for a full explanation.

This is, however, a nuanced argument and I’m happy to explain and clarify. It’s not complicated, but does require taking a little deeper analysis.

Yes, Virginia, the Chupacabra Dates to 1995

No one disputes that vampire reports and legends are a global phenomenon; that’s why my book begins with a chapter on vampires around the world, ranging from ancient Mesopotamia to revenant vampires in Middle Ages Europe (the kind who were staked in their coffins by fearful villagers) to vampire varieties in Africa and South America. Those vampires had different characteristics and went by many different names.

These typically emerge from specific regions and locations (the likichiri in Bolivia, for example, is not the strigoi in Romania, and so on). They’re all subtypes of vampires, but they are separate and distinct; they are not the same thing, and we confuse them (or lump them together) at our peril. Thus we can accurately say that the chupacabra did indeed suddenly emerge in Puerto Rico in 1995; or, if you prefer a more technically accurate version, that “a type of vampire called the chupacabra, with several distinct characteristics associated with it, both at the time and later” was first reported in 1995.

Were there earlier (pre-1995) reports of vampires, both in Puerto Rico and around the world? Of course there were; everyone knows this. It’s not accurate to assert that because a vampire had been reported on the island before 1995, that the chupacabra, specifically, had been reported—or that they were (or must have been) the same thing. They were not.

The Vampire of Moca: Early Chupacabra?

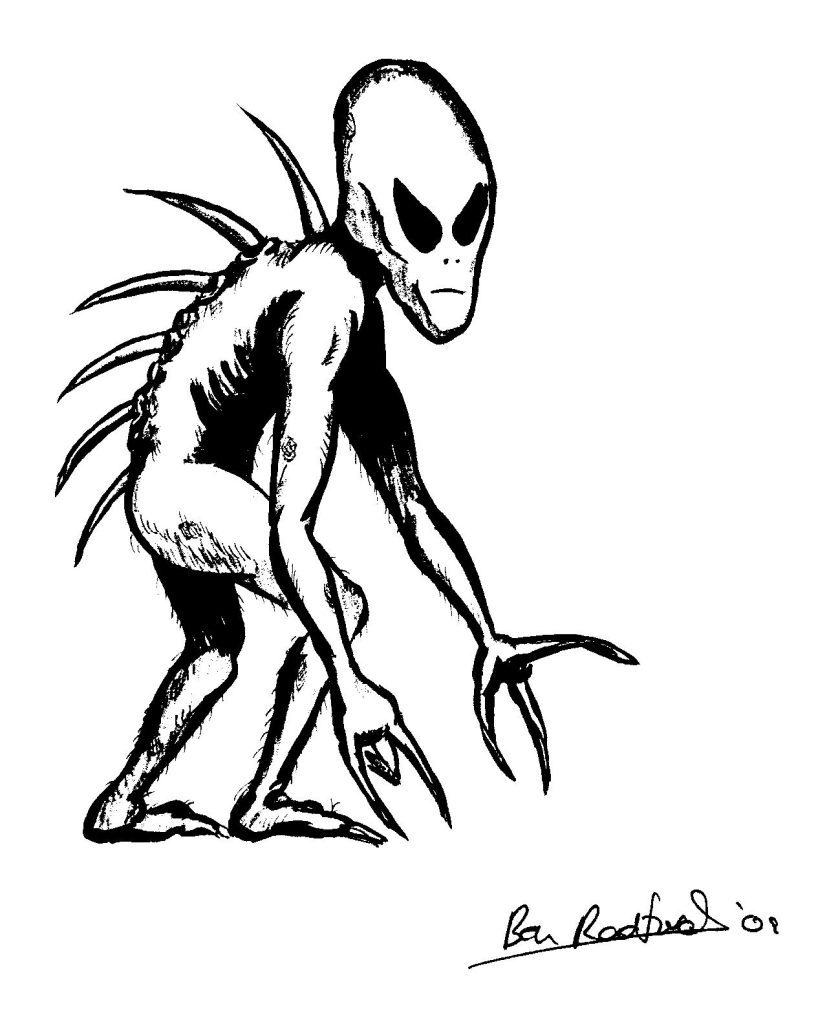

Let us return to the example of the pre-chupacabra Puerto Rican vampire Redfern offers. The famous “vampire” cited as a predecessor to the chupacabra relates to attacks in the city of Moca in 1975 and references his time spent there with a TV crew. Redfern mentions a report of a woman clawed by “what she described as a fearful-looking beast covered in feathers,” and also “a huge, winged monster” that landed on a home’s roof. It’s all suitably dramatic, but a very different beast than the one that would be described and named some two decades later on the other side of the island—which was rarely, if ever, described as having a feather-covered body or wings (nor for that matter, was it “huge”). When I interviewed the original chupacabra eyewitness she described it as a small (three-foot) humanlike figure with long arms and legs and alienlike, wraparound eyes and spikes down its back (see illustration below); later incarnations after 2000 were canid (such as coyotes and foxes).

Chupacabra illustration by Benjamin Radford

A huge, feathered “chupacabra” does not match descriptions from 1995 (with the exception of spine spikes with featherlike striations). Plus the earlier creature already had a name: El Vampiro de Moca, the Moca Vampire.

I had also visited Moca during my research, in the interest of leaving no vampire story unturned. There’s simply no clear link between the Vampire of Moca and the chupacabra. Not only are the descriptions different, but the Moca incident was not the first example of “mysterious” predation in Puerto Rico. Furthermore, if the Moca Vampire and the chupacabra are the same animal, then it is hard to understand the creature’s two-decade fast between meals. It makes no sense that a “goatsucker” would kill a handful of animals with perhaps a gallon of blood between them in 1975 and then vanish for twenty years before suddenly reappearing and deciding to resume its quest for blood. (As I note in Tracking the Chupacabra, a nearly identical “chupacabra-like” incidents occurred a year earlier, in 1974 Nebraska and South Dakota. Eyewitnesses reported seeing “a monster-thing,” presumably having attacked cattle and drained their blood.) He’s incorrectly lumping the two phenomenon into one.

Claiming that the chupacabra existed before 1995 merely because there were earlier vampire reports is like saying that the Fouke Monster existed before the 1950s (when it was first reported)—or that the Honey Island Swamp monster existed before 1963 (when it was first sighted)—because Bigfoot reports (allegedly) date back a century or so earlier.

This is not a pedantic “debunker” argument, but instead a key lesson in cryptozoology. In their book The Field Guide to Bigfoot, Yeti, and Other Mystery Primates Worldwide, Loren Coleman and Patrick Huyghe lament a common mistake in cryptozoological research, a “lumping problem,” that is, that myriad sightings of different, distinct creatures are lumped together under more general names such as Bigfoot or Yeti. This, they write, is a problem because it “hides a larger truth, lumps considerable differences, and just plain confuses the picture.” Lumping the chupacabra with the Moca Vampire is precisely the fundamental error Coleman and Huyghe describe.

As a comparison, Bigfoot (generically, as an unknown, hairy, bipedal hominid) reports existed before the Bigfoot-like Honey Island Swamp Monster was first reported in 1963, but that doesn’t logically mean that Honey Island Swamp Monster was described (or existed as its own entity) before 1963. The Fouke Monster can fairly be said to have first appeared in the 1950s; Mothman can fairly be said to have first appeared in 1966, and so on. For the same reason, the chupacabra can fairly be said to have first appeared in 1995. It’s not complicated.

So when I (and the internet, when it quotes me) say that the chupacabra first appeared in 1995, that is completely accurate: The chupacabra—as a specific variety of vampire unique to Puerto Rico—was first seen, named, and described in 1995. Not 1994, not 1985, not 1870. The true story of the chupacabra story is fascinating enough—involving conspiracy theories, vampires, creationists, and science fiction thrillers—without adding on myths and misinformation.

0 Comments