My new article is about the new Netflix documentary ‘Misha and the Wolves,’ which examines a famous and bizarre literary hoax: A woman claimed to have walked across Europe and been raised by a wolf pack while searching for her parents during the Holocaust. Her book became a worldwide bestseller, until troubling questions were raised about her story. The film is about history, identity, authenticity, betrayal, and why we choose to believe…

The new Netflix documentary film Misha and the Wolves examines the life story of a Holliston, Massachusetts, woman named Misha Defonseca who stunned her congregation decades ago on Holocaust Remembrance Day by breaking her silence about her past: She was not only a Holocaust survivor, but as a young girl had fled her home in Belgium and walked to Germany in search of her parents, last seen in concentration camps. That was remarkable and brave enough, but she hadn’t done it alone; “She had trekked nearly 2,000 miles across Europe in the middle of winter to search for her parents, and on this journey had been saved from death by a pack of wolves who had taken her in and raised her as their cub. She recalled how, while she subsisted on a diet of wild meat and scavenged scraps, she sometimes heard terrible sounds coming from deportation trains and once had to kill a German soldier with her bare hands when her life was in danger” (Katsoulis 241).

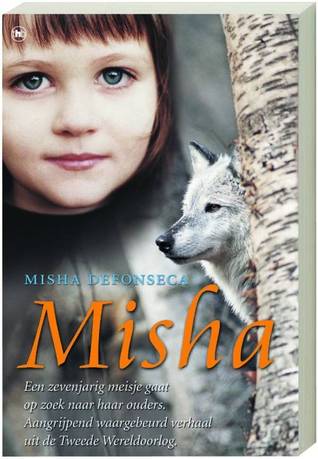

Misha’s incredible story caught the attention of a friend who ran a small publishing house, Jane Daniel, and was soon turned into a best-selling 1997 book titled Misha: A Mémoire of the Holocaust Years. It caught the influential (if not particularly discerning) eye of Oprah Winfrey, and would later be published in several languages and optioned for films. Misha became a celebrity, touring the world telling her inspiring story of courage and overcoming adversity.

Eventually, however, some suspected that her story was in fact literally incredible—not credible. Misha and the Wolves expertly describes the rise and fall of Misha’s story. Even though I’d read basic outlines of the events, there were some surprising plot twists that I won’t reveal, as there are enough spoilers already. It’s not just the story of a strange story of a suspected hoax, but perhaps more importantly, it’s the story of people who joined forces to reveal the truth.

The public is of course widely—and rightly—counseled to “believe the victim” in many circumstances. That is the appropriate default position for any plausible claim, and the vast majority of the time the victim is as claimed. Most of the time people, by default, believe what others tell them (see Timothy Levine’s work on Truth Default Theory). This extends to claims of victimization as well; contrary to popular belief, women who come forward with claims of victimization (including by public figures) are generally believed, not doubted.

But in some cases it’s not clear who the victim is (or if there really is a victim at all), and the film explores the continual trepidation of those who questioned Misha’s claims: what if they were wrong? No one wanted to be in a position of casting doubt on the account of a true victim, and especially not of the Holocaust. This reluctance to question victims can of course be seen in many other contexts; see for example the 2012 documentary The Woman Who Wasn’t There, about a woman who claimed to have survived the Twin Towers collapse on 9/11/2001, and—like Misha—became a spokeswoman for the cause of remembrance and honor for the tragic events, heading a survivors group.

Misha’s deception would likely have never been revealed but for the tenacity of not only the book’s original publisher, Daniel, who was sued (and, as it turns out, wrongfully awarded millions) by Misha, but also a genealogist, a journalist, and others. The fact that Misha was invited to appear on the Oprah Winfrey show to promote the book but declined was, ironically, one of the early red flags that something wasn’t right. Oprah, it should be noted, has a long history of promoting heart-tugging memoirs that were later revealed to be largely or wholly hoaxed, along with untold numbers of other dubious and discredited topics. For another Oprah-promoted fake Holocaust story presented as tear-jerking memoir see Herman Rosenblat’s book Angel at the Fence.

The film builds suspense as each new piece of information is revealed. Misha and the Wolves is a story of remarkable detective work, deception, and gullibility and unfolds like a series of Russian dolls, spinning into several smaller mysteries: Is Misha’s story mostly true, like anyone’s subjective recollections and allowing for mistakes, memory lapses, and biases?

Within about twenty minutes (or sooner, if you’ve seen any coverage of the case) it’s clear that Misha’s story isn’t true—or at least isn’t entirely true. But is that significant? Authors James Frey and Joe Mortensen, among many others, eventually admitted to fabricating key parts of their bestelling memoirs, A Million Little Pieces and Three Cups of Tea, respectively. So did Nobel Prize winner Rigoberta Menchu in her book I, Rigoberta Menchu, but all of them insisted that the books were mostly true.

Or is it entirely fabricated, and if so, to what end? Was it akin to the influential 1971 young adult memoir Go Ask Alice, which was completely made up by an evangelical middle-aged Mormon woman trying to teach moral lessons? Or is she delusional, perhaps (understandably) traumatized by the war? If Misha didn’t spend her childhood living with wolves and walking through forests to find her parents, then where was she? Surely there would have to be some record, somewhere…

It is perhaps fitting that the real heroine of the film—the person who does indeed find the smoking gun (though where and of what I won’t reveal)—is herself a Belgian Holocaust survivor named Evelyne Haendel. Holocaust memorial organizations are in fact among the most skeptical of such claims, precisely because a handful of people have falsified their experiences, and accepting claims without due diligence dishonors real victims. Holocaust historian Debórah Dwork also provides insight into the complexities of truth and doubt.

Writer and director Sam Hobkinson does a masterful job of letting the participants speak for themselves, with one notable exception (revealed in a twist reminiscent of the 2019 documentary Wrinkles the Clown), revealing conflicting agendas at virtually every turn. Publishers and journalists want a good story; historians and genealogist want the truth; and documentary filmmakers want a blend of both. Misha had her own reasons for creating the story, and others had their own motivation for turning a blind eye—or not—to potential deception. Jane Daniel, it turns out, was warned by at least one expert prior to publication that Misha’s story was dubious. Nevertheless the promise of notoriety and wealth won out, until the time that it served Daniel’s interest to take a closer look at the remarkable story she’d helped launch into the world.

Misha and the Wolves is curiously reminiscent of another documentary series, also on Netflix, titled The Devil Next Door, out in 2019. That five-part series tells the true story of another elderly, otherwise unremarkable American citizen with murky (and contested) ties to the Holocaust: Ivan Demjanjuk. The retired autoworker settled in Cleveland and was later accused of being a prison guard at a Nazi concentration camp nicknamed “Ivan the Terrible” by his victims. But was he? As the series reveals, the answer is yes and no.

The ‘Wild Child’ Myth

Misha’s story was especially compelling because it drew on two popular and powerful narratives. The Holocaust survivor narrative and the wild or feral child stories. Stories and legends from around the world tell of children raised by wild animals including wolves, bears, and apes.

The feral child is common in myth and folklore, dating back at least to Romulus and Remus, the twin brothers of Roman mythology rescued from certain death and raised by a wolf. The feral child image evokes a strong romanticism for many people, and this was especially true at the turn of the last century. Rudyard Kipling made a hero of the feral child Mowgli—an Indian boy raised by wolves—in his classic and wildly popular 1894 collection of stories The Jungle Book. Misha: A Memoir of the Holocaust Years is an example of this. Though not a feral child story per se, Misha’s story evokes the purity and innocence of the animal world as metaphor, and contrasts it with the evil that human genocide can bring.

Misha in Context

When questioned, Misha doubled down and dismissed skeptics for years, daring them to debunk her narrative. When the deception was definitively revealed, Defonseca “apologized unreservedly to the readers who had bought her book in good faith, and in the now familiar terms of a hoaxer pleading an alternative truth as a reason for their deception, went on to say, ‘There are times when I find it difficult to differentiate between reality and my inner world. The story in my book is mine. It is not the actual reality—it was my reality, my way of surviving’” (Katsoulis 246).

In a March 9, 2008, New York Times opinion piece, Daniel Mendelsohn notes that Misha: A Memoir of the Holocaust Years is “a fraud far more reprehensible than Mr. [James] Frey’s self-dramatizing enhancements [in A Million Little Pieces]. The first is a plagiarism of other people’s trauma. Both were written not, as they claim to be, by members of oppressed classes (the Jews during World War II), but by members of relatively safe or privileged classes. Ms. De Wael [writing as Misha] was a Christian Belgian who was raised by close relatives after her parents, Resistance members, were taken away… a comparatively privileged person has appropriated the real traumas suffered by real people for her own benefit—a boon to the career and the bank account, but more interestingly, judging from the authors’ comments, a kind of psychological gratification, too…. Ms. De Wael has similarly referred to a longing to be part of the group to which she did not, emphatically, belong: ‘I felt different. It’s true that, since forever, I felt Jewish and later in life could come to terms with myself by being welcomed by part of this community.’ (‘Felt Jewish’ is repellent: real Jewish children were being murdered however they may have felt.)”

The post-truth defense rang hollow to others as well. Adopting a cultural studies approach, Anne Rothe states that “Defonseca’s fabrication is revealing because it indicates the extent to which readers are willing to suspend their disbelief and to accept in a supposed Holocaust memoir that a young girl could walk across Europe in the midst of the Second World War and even that she was adopted by wolves… It is also illuminating because the ensuing legal battle…constitutes the clearest indication to date of the vast commercial potential of representing the Holocaust as an ahistorical, kitsch-sentimental horror fantasy of trauma and redemption in contemporary Western culture” (142). For more on this fascinating case see Telling Tales: A History of Literary Hoaxes, by Melissa Katsoulis, and Popular Trauma Culture: Selling the Pain of Others in Mass Media, by Anne Rothe (full disclosure: I’m referenced in the latter book). Also check out Squaring the Strange, episode 112, on literary hoaxes.

Misha and the Wolves is rife with lessons on critical thinking, skepticism, and confirmation bias. The film also highlights the dictum about how it takes exponentially more effort to debunk falsehoods than it does to create them—and how the burden of proof is often tacitly shifted from claimant to investigator. This is excellent documentary filmmaking, and about much more than one woman’s audacious hoax or delusion; it’s about history, identity, authenticity, betrayal, and why we choose to believe.

A longer version of this piece appeared on my Center for Inquiry blog; you can read it HERE.

0 Comments