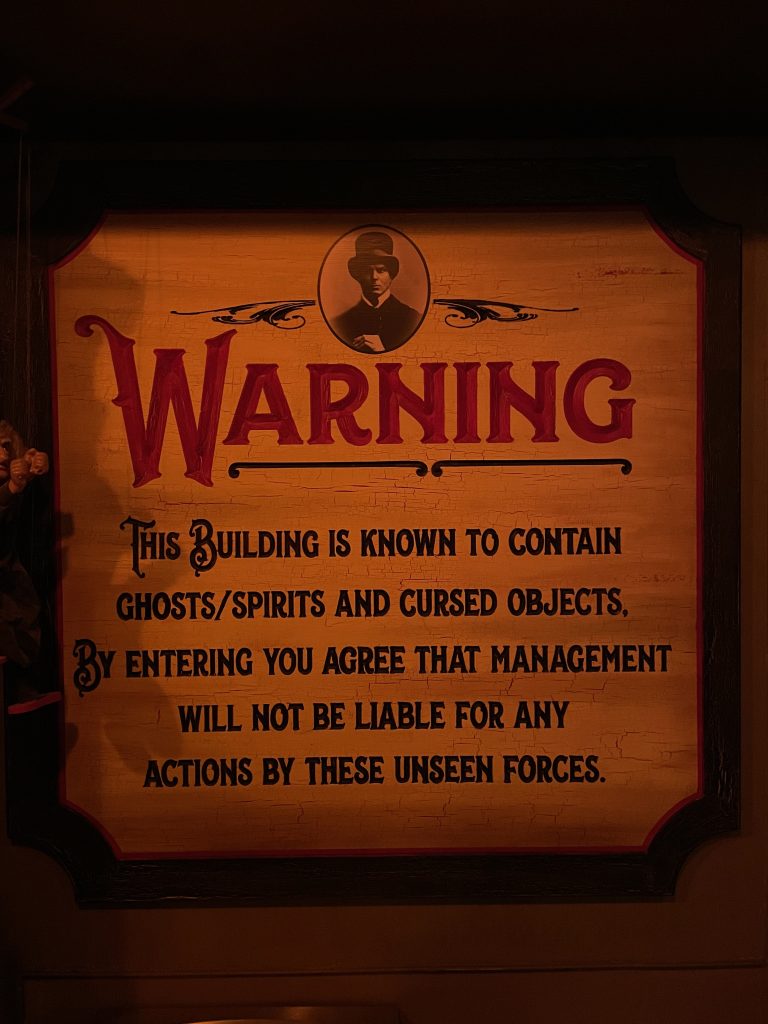

During a recent visit to Las Vegas, Nevada, a few friends and I got the chance to visit the Zak Bagans Haunted Museum, said to house some of the most powerful and dangerous objects in the world, curated by the ghost-hunting star of several popular series including Ghost Adventures on the Travel Channel. We had several noted skeptics including Ian Harris, Susan Gerbic, and Kenny Biddle with us. Photographs were strictly forbidden during the tour itself, though we were allowed to take pictures outside and in the entrance room.

While waiting outside I took some photos and was later stunned to discover a strange haze or mist that seemed to envelop Kenny. It looked similar to many ghost photos that Kenny and I had investigated (and debunked).

Sometimes those images can be accidentally created by cigarette or vaping smoke—yet no one in our group or nearby was smoking. In other cases, a person’s breath on a cold day can mimic the smoky haze—but it was warm and midday. Adding to the mystery, Kenny reported that he felt a chill in the air, as if the otherworldly ectoplasmic mist was somehow drawing energy from around him in order to manifest—and potentially harm him or someone else.

Before we could investigate, we were ushered into the museum—and right past Zak himself, who (thanks to our clever disguises and pseudonyms) didn’t recognize either of us, or anyone else in our party. We then filled out a bunch of releases and embarked on a nearly two-hour tour.

There are too many exhibits to enumerate, and Kenny Biddle has done an excellent job of investigating some of the most prominent “haunted” objects on display there, including a haunted guitar, a supposedly haunted mirror once belonging to Bela Lugosi, and perhaps most prominently, the infamous dybbuk box which may or may not be among the most powerful evil objects in the universe.

There were some items that I was familiar with, including the famous Crying Boy prints that folklorist David Clarke expertly explained and investigated years ago (for more on this check out his appearance on the Squaring the Strange podcast). The write-up on the haunted item, of course, made no mention of any skeptical or scientific explanations.

Another item on display which I’d researched was the “James Dean Death Car” involving the transaxle from James Dean’s 1955 Porsche 550 Spyder (nicknamed “Little Bastard”), allegedly the same vehicle that Dean was driving when he was killed in a car crash on September 30, 1955. Bagans claims to have spent $382,000 on the piece, which is one of the car parts that has supposedly injured or killed several people who owned them or used them in their vehicles.

Writer Jason Colavito poured cold water on the James Dean exhibit. Writing on February 12, 2022, he noted that

Given that Bagans promised that the exhibit would celebrate Dean’s life, not just linger on his death, the grotesque fixation on his demise is a disappointment. As we look around the “exhibit”—rather, the transaxle assembly, a terrible bust, and a collage—we note the life-sized photo of the crashed Porsche, but also the lack of any obvious narrative or context. It’s just a picture of car crash and a chunk of wreckage, mounted like some type of automotive crucifix. The adjacent wall is still worse. It contains what at first glance seem to be news clippings about Dean’s death. But on closer inspection, they are not. The New York Times front page with the banner headline about Dean’s death is a fake. The real Times ran a spall interior piece on the actor’s death the day after. Another clipping is the cover of W. Scott Poole’s book on Maila Nurmi, TV’s Vampira, which has only a tangential connection to Dean. A bit of the 1956 tabloid story alleging Vampira had witchy powers she used to curse Dean appears, as does an alleged newspaper story claiming that Little Bastard killed “more” people. Since the car’s parts allegedly killed just two others besides Dean, it’s not clear who the “more” are. The text appearing in the article on the wall is word-for-word copied from a blog post last updated in 2020. Bagans’s unconvincing mockup is an obvious fake.

It’s a grotesque collage, both promoting a sexist bit of 1950s rumormongering and all but celebrating Dean’s death. As a supernatural exhibition, it lacks imagination. Many supernatural stories have been told about James Dean, so why choose the most obviously fake one, except that it’s the first thing Bagans found in a Google search? A richer exhibit might have presented a range of supernatural stories about Dean, from alleged posthumous psychic contact to, ghostly apparitions, to, yes, supposedly haunted car parts, and asked a serious question about why so many people—thousands, by one count—think they have had supernatural experiences with the dead star. The only real competition is the rash of 1980s sightings of Elvis in 7-Elevens.

Lee Raskin, author of James Dean On the Road to Salinas, notes that most of the stories about the curse originated with a car customizer known for telling tall tales; indeed as one article put it, “Raskin is convinced that most of his stories were fabrications, and several are demonstrably false.” Nevertheless, the truth never stands in the way of a good story (or a quick buck) and Bagans was happy to buy and present it.

I had several reactions to the museum, chief among them that it contained a lot of material that was at best tangential to anything spooky or ghostly. It’s packed with random stuff, including clowns, dolls, guns, sideshow freaks (such as some two-headed animals), old stuff, and so on. There is a lot on circuses, including a diorama, which is okay but has nothing really to do with evil spirits or ghosts. In several places they had surveillance videos of people passing out while on the tour, and of course this was attributed to evil spirits instead of the fact that it was hot and stuffy throughout most of the tour, with no place to sit or rest.

It’s 60% random “weird” or “creepy” stuff, about 30% murderabilia, and about 10% of the museum are objects that—assuming they are authentic, which is not at all likely—may have some genuine interesting story. As Susan Gerbic noted in a conversation afterward, there is, arguably, legitimate historical interest in some of the objects on display. Whether personal effects (allegedly) belonging to serial killers and mass murderers such as John Wayne Gacy and Charles Manson are important or relevant is up for debate, though the van that Jack Kevorkian used in carrying out his assisted suicides is also on display. Was the cauldron on display really owned by serial killer Ed Gein? (Maybe?) Did it ever have any of his victims’ bodies in it? (Maybe?) For more on the experience, check out our recent episode of Squaring the Strange.

Exploiting the Dead

The sensational and exploitive nature of some of the exhibits was, while not unexpected, distasteful. I have encountered this several times over the years. In my investigation of the haunted KiMo theater in Albuquerque, New Mexico, I was contacted by a relative of the boy, Bobby Darnall, who died there. Stories of his ghost have haunted the Darnall family for decades. His sister and brother feel exploited by the story and do not appreciate the fictional claims that their beloved brother is a resident poltergeist ruining performances at the theater.

In my investigation into Jamaica’s Rose Hall Plantation (the subject of Chapter 12 in my book Scientific Paranormal Investigation and the 2015 season premiere episode of the Travel Channel show The Dead Files) I revealed that the evil woman widely claimed to haunt the mansion—Annie Palmer, the so-called White Witch—was in fact based on an innocent historical person. I asked readers to consider the feelings of others: “Imagine if, a century from now, due to some strange mix of myth and circumstance, people describe you as a cruel, perverted, sadistic serial killer. Psychics and ghost hunters claim to contact your spirit, and relay your sensational confessions to the public.” How would you feel to have your good name ruined by sensational, ill-informed ghost hunters who claim to contact your spirit and perhaps elicit a “confession” to murder, sexual abuse, or worse?

Bagans released music that he claims includes the voice of a television actor’s ghost. According to a press release issued on behalf of Bagans and reposted on several Web sites, “In 1999, actor David Strickland, best known for his role on the NBC sitcom Suddenly Susan, committed suicide in room 20 of the Oasis Motel in Las Vegas. More than a decade later, Zak Bagans, the host and lead investigator for the hit TV series Ghost Adventures, spent hours in that very room attempting to establish communication with Strickland’s departed soul. The results of that investigation can be heard on the track Room 20 from NecroFusion, the album from Bagans and musical partner, The Lords of Acid’s Praga Khan.” I found that CD on sale in the gift shop.

According to Bagans he went to the motel and “after hours of recording sessions… I began communication with mind-blowing responses. One of the responses I got was when I said ‘hello’ to David, and a male voice who I believe was his, replied ‘Hi, Zak.’ I asked if he could hear me and he said ‘yea.’… I asked him if he knew where he was, and told me the name of the hotel… Oasis. This was one of the most powerful spirit communication sessions I have ever conducted.”

Bagans offered no scientific evidence for his claim. But assuming for a moment that Bagans did in fact contact a ghost, how does he know it was actor David Strickland? Several other people are known to have died violently in that Las Vegas hotel, including murderer Theodore Sean Widdowes in 1996 and professional poker player Stu Ungar in 1998. In fact given the sketchy area of Las Vegas where the Oasis is located, there might be dozens of people who died nearby by murder, accident, or suicide over the years— any or all of whom could presumably haunt the motel. Yet Bagans somehow positively identified a few short, muffled, ambiguous bits of words (what he hears as, “yea,” “Hi Zak,” “Oasis,” etc.) as spoken by Strickland’s ghost.

If what Bagans claims is true, he may have a unique opportunity to prove skeptics and scientists wrong, and show once and for all that EVP really are ghost voices instead of an auditory illusion. If the sounds that Bagans recorded are indeed the voice of deceased actor David Strickland, it should be easy enough for an audio expert to compare the EVP to voice samples taken from Suddenly Susan or any other of Strickland’s television appearances. Either the sounds that Bagans recorded match Strickland’s voice or they don’t. Strangely, despite being “one of the most powerful spirit communications” Bagans has encountered, such a basic analysis was apparently never done. It’s unclear how David Strickland’s family felt about his tragic suicide (fueled by the actor’s drug addiction and mental illness) being exploited as entertainment by Zak Bagans.

Everyone likes a good story, and ghost hunters especially love a creepy and compelling ghost story. Truth is often stranger than fiction, but ghost hunters must be sensitive to the people (with lives, loves, and families) behind their stories. Real people and reputations can be harmed—and the dead dishonored—by careless investigation. Ghost hunters have an obligation, to both the living and the dead, to act ethically and responsibly.

On the tour we also saw a strange replica of the Titanic, in the same room as a display about Natalie Wood; if you’re thinking the connection between the two is tenuous, you’re right. Toward the end of the tour a huge painting of P.T. Barnum is on display. Bagans is said to idolize Barnum, which makes sense, and it’s clear that Bagans’s career is built largely on lessons learned from the consummate showman. Barnum was not an investigator but an oddity collector, and proud fast-talker who freely mixed the real and the fake together as long as he could make a buck and promote the brand; as Barnum surely believed—though may not have actually said—there’s a sucker born every minute.

Knowing that Zak Bagans was caught in a recent plagiarism scandal by Kenny, I innocently asked the gift shop employees where his book Ghost Hunting for Dummies was. The woman said she didn’t know, but they just had what was there on the table. I thought about informing her that the reason they didn’t have the book was that the publisher was forced to recall the book and credit the real authors that Bagans—and or his ghostwriter, Troy Taylor—had somehow omitted.

The guides were well-prepared and well-rehearsed, important because there are cameras everywhere and Zak is said to sometimes listen in on tours and berate guides through earpieces if they flub something. In the end, though the museum itself was mostly a boring bust, we were still baffled by the strange misty form that appeared in the photo of Kenny just outside the museum. We may never know what, exactly it was—or whose tortured spirit may have been reaching out to him from beyond the grave at what’s widely described as the most haunted place in the United States, or even the world. We may send it to Zak and ask him to investigate.

0 Comments